Nosferatu and the Reality of Horror

As usual, this blog keeps up with the bleeding edge of culture.

We speak of being “taken out of” a horror film when we are unduly reminded of its being a film—the boom mic dips below the top of the frame, an extra playing a corpse shifts to get comfortable, the plastic edge of an axe emerges from a papier mâché wound rimmed with ketchup—and consider this a fault of a film, at best a cause for ironic enjoyment of a cheap production.

What exactly it means to be “in” versus “out” of a film is a matter of some subtlety. It’s not like the audience ever actually forgets they are sitting in a darkened room, looking at a screen—otherwise, William Castle’s promotional gimmick for Macabre of offering $1,000 life insurance to any viewer who died of shock might really have had to pay out—we are really talking about the fluidity of pretense, and so really something that comes in degrees. Digital blood splatter may take some viewers out of a film, but for a briefer period, a lesser extent than catching the production crew reflected in a mirror.

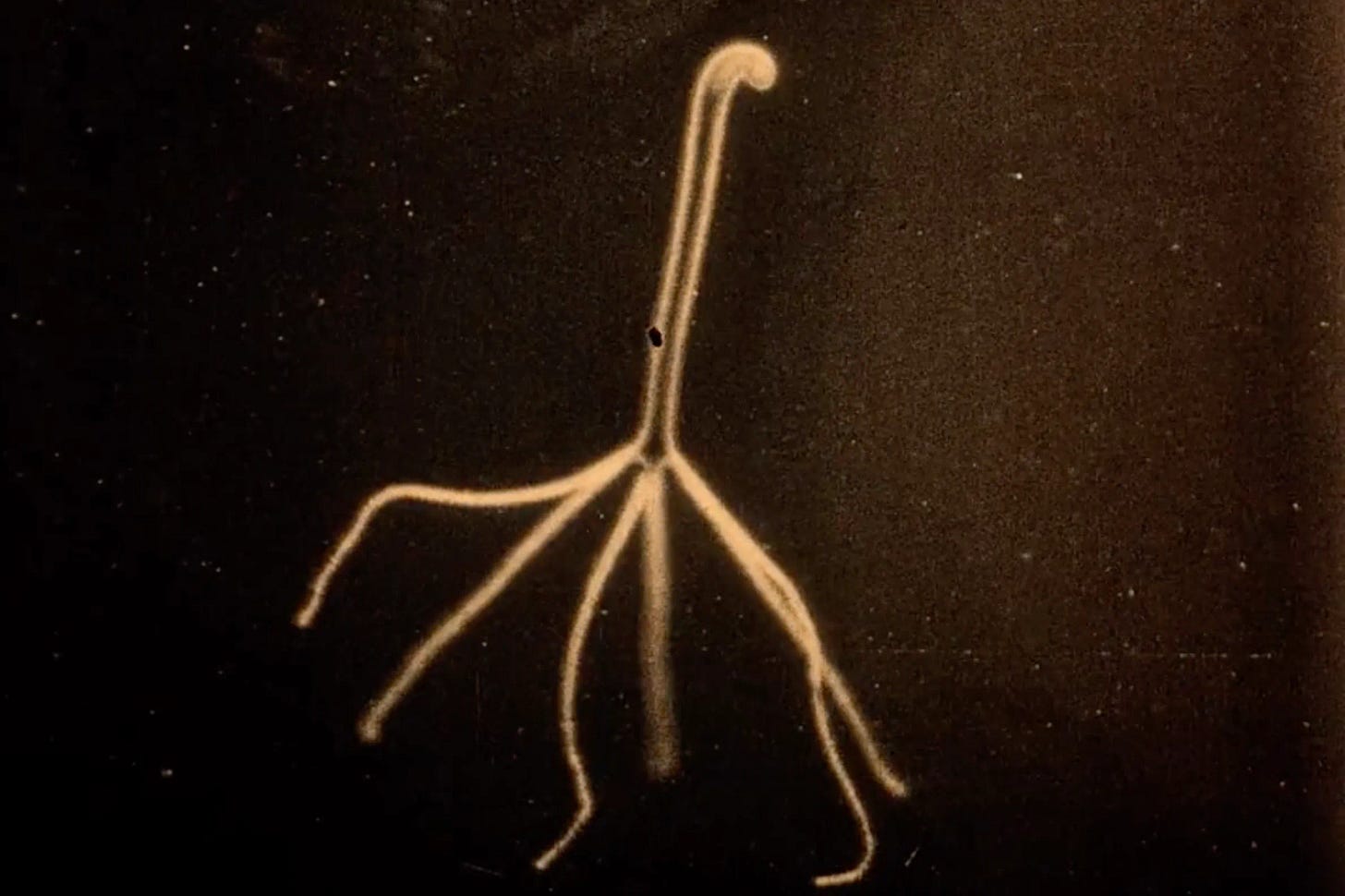

Being “taken out of” a film in this way we may think of as going behind the screen. But we can also be taken out by going through the screen. A clear example of this occurs in the original Nosferatu (1922) with a scene in the middle of the film cutting to documentary-like footage of a polyp. (Here’s the scene on YouTube.)

To fill in the context. Nosferatu was an adaption of the Bram Stoker novel Dracula, which the filmmakers, in an attempt to avoid paying for the rights to the film, transplanted to Germany and renamed characters (e.g. Count Dracula became Count Orlok). This attempt failed, the production company was sued by Stoker’s widow out of existence and ordered to destroy the film. Certain prints slipped into America and, thanks to a quirk in U.S. copyright laws at the time, avoided this court-ordered oblivion.

Since we will be discussing two remakes of Nosferatu in a moment, a quick plot summary will help orient us. We open with a recently married real estate agent going to Transylvania to sell a decrepit German estate to an eccentric noble. This noble is, in fact, a vampire and the protagonist’s boss is the vampire’s minion. In the vampire’s castle, the vampire sets his eyes on the hero’s wife; barely surviving his encounter, the hero races the vampire back to Germany.

Since the vampire is cursed to have to sleep in the soil he died and was reborn as an undead in, he ships himself inside his coffin by sea. Along the way, he kills the entire crew of the ship with a plague, which spreads throughout the city when the ship lands. The husband arrives home in a weakened state; it is up to the wife to deal with the supernatural menace. She accomplices this through a sacrifice of her own life, giving herself to the vampire to feast on her blood. She keeps him there as the sun rises, whereupon the curse kicks in and he is destroyed.

Worth noting is that the scene that we are concerned in appears no where in this plot summary. In the story it serves solely as an introduction to a minor character: a scientist who is among the secular authorities dealing with the plague after the vampire arrives. The scientist displays the polyp to his students, describing it in a mixture of naturalistic and quasi-supernatural terms, “a polyp with tentacles,” “almost a phantom,” as the polyp consumes some other microorganism.

This digression of a scene is cut against another: the interrogation of Herr Knock, the vampire’s lackey and the hero’s boss, who has, as far as anyone can tell, gone stark mad and raves about the coming of his master. Locked in a cell in his asylum, the gentleman has taken to raving about blood. Knock points out a spider eating a fly and the camera points to it, framing it in the same cool, documentary style as it applied to the polyp.

In the story, these paired scenes invite an implicit comparison. Both Knock and the scientists imagine themselves as atop nature’s pyramid of death—the scientists because of their understanding, Knock because of his alliance with Death itself. Both are mistaken, but not completely so. The scientists’ ladder has no rung for a vampire, and yet he is in a way just another predator, some exotic species awaiting cataloging. And Knock is right that his master will come and bring death, wrong that he will be rewarded for his subservience, wrong that his side will triumph.

It is in the end, though, not this narrative and thematic context that is most striking about the polyp. Rather, it is that for the seconds that it is on screen, I am taken out of the story but deeper into the film. It feels like I am examining this creature through a microscope. The flatness of the screen makes an almost perfect substitute for the flatness of a petri dish. The unrehearsed, unsettling movements of the polyp bear no relationship to the mannered, expressionist horrors of the rest of Nosferatu: this is a real monster!

We might describe things this way. Any film leads a double life. It is at once a story, something for the viewer to watch, to play along with, and also a series of photographs of real objects taken at specific times (plus post-processing). The viewer is always more or less aware of that second aspect, but that awareness can take two different objects. They might be aware of the artificiality of the image, of how it is contrived, but they might also be aware of the reality of the image: that the camera is after all capturing objects in a light that was really there.

Specifically in the context of horror, this last awareness can be especially potent. We will have to go on a short journey to see how this is.

For philosophers of art, horror has proved an especially puzzling genre. Being terrified, fearing for one’s life, seeing something upsettingly visceral—these are negative experiences in reality, to be avoided where possible. Yet people go crazy for horror fiction, enjoying what one might otherwise think to be negative emotions: fear, anxiety, disgust.

We won’t solve this “paradox of horror” here. We can merely note that the safety of the fourth wall is a part of any reasonable account. The fear one feels watching a horror film is not a true or at least a full fear. It is only a pretend or at least a qualified fear. The audience, after all, is simply sitting comfortably.

And yet the fear horror films inspires cannot completely be qualified away. After all, though the scenes that terrorize are securely fictional, the basic terrors that animate those scenes, the terrors of suffering and death, are very real. Furthermore, while this safety may be an essential to the appeal of horror, it is not itself an appeal. That is, the audience does not want to be more safe—flubs that take one behind the scenes in a horror film are generally flaws—and often prefers being less safe.

Going through the screen in the way described frays the safety of the fourth wall. We have to confront in a much more direct way the thing that scares us.

The greatness of Werner Herzog’s 1979 Nosferatu is largely how it develops this naturalistic aspect of the original. Repeatedly throughout the film, the images on screen exist as elements of fiction and as themselves. Sometimes this is simultaneous. The rats, for instance, that attend Count Orlok, exist both as plague rats in the story and as real rats captured on film in one and the same shots.

And at other times the images flit back and forth. The castle exists as a supernaturally twisted place, a host to a demon, when filmed at night, and more as a physical construction when seen in the daylight. In either case, the effect is to take the viewer out of the story, but in a way that we will see is productive.

The story of Herzog’s Nosferatu is largely identical to that of the original, apart from a divergence in its final few minutes. In terms of its style, the film keeps a small portion of the expressionist imagery of the original and trades the rest for something that alternates between documentary and visionary.

Carried out in this consistent manner, the effect of the film is that of a divided intelligence. With half of its mind, it is pursuing the thread of the story, the world of vampires and plagues and 19th century. With the other half, the real world of rats, disease, political upheaval. These parts are not separate but constantly meeting and diverging in the same set of images.

At the center of these doublings is Count Orlok. He is at once the same demon as haunted Mernau’s original—most of the images repeated from the original are those surrounding Orlok—and yet also a metonym for European aristocracy, and also a physical person who happens to be crossing the camera. This last aspect owes itself to Klaus Kinski’s moody performance, Kinski being an all-time mess of a human being.

There is no difference in terms of technique between a moment of a film that takes us behind-the-scenes versus through-the-screen. The brightness of the castle, for instance, how pleasantly the trees appear through the window in Herzog’s Nosferatu, for instance, could just as easily distract the audience as a shoddy presentation of a set as it could impress us as a breaching of thought out into the physical world of the feudal system’s decaying aftermath. Indeed, perhaps for an unsympathetic audience it will merely distract.

There are aesthetics risks here, undoubtedly. The reward of a film’s leading us through the screen is a moment of direct and palpable connection. When Ellen, the hero’s wife, for instance, walks through the city square during the plague, with its carnival of death and desperate gasp of jubilation, the camera distant, wandering through seemingly uncomposed stretches of rats and pigs and peasants, we understand not merely what is happening to a character in a moment of a story, but what it is like to live in the last gasp of a civilization.

It is only right to end this discussion with the most recent remake of Nosferatu, Egger’s 2024 film. This movie stands as an entirely negative example of the current topic. The fourth wall never slips. The film is instead immaculately styled and obsessively constructed to flesh out its style. The story and most of its principal players have been given more to do, greater depth. The world has been realized with a fanatical attention-to-detail and a high sheen.

The point of this essay is not that taking the audience through the screen is the only or even a superior method of providing meaning. It is not a fault of this most recent Nosferatu that it does not. Yet given how much this Nosferatu takes from the original, and given how richly Egger’s other films take from their historical realities, I cannot help but find it a shame that it remains safely ensconced in its fictionality, how aestheticized the history is.

It is worth perhaps dwelling on this difference. We may get somewhat closer with one of the more trivial bits of discourse surrounding the film: Count Orlok’s moustache. Some commentors found the moustache distracting on such an otherwise movie-monster design. Meanwhile, the moustache arrives at the consequence of a simple historical syllogism: Orlok is a Transylvanian noblemen from the 15th century, all Transylvanian noblemen from the 15th century had facial hair, ergo Orlok has facial hair.

What this detail suggests is that this most recent version has a particular commitment to a sense of verisimilitude, of truth-likeness, despite its fantastical, fairy-tale plot. Yet there is an enormous difference between saying something logically grounded in a reality and saying something true. In fact, it is where the previous versions most breached their own reality, depart from a sense of consistent fiction, that they are most able to be truthful.