Tell It Slant

The necessary illusions.

[Tell all the truth but tell it slant —]

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

I have finally staked out some time to participate in ModPo, which is now looking at some Emily Dickinson poems. This poem reminded me of an essay by a different Emily.

In order to be happy, one must have freed oneself of prejudices, one must be virtuous, healthy, have tastes and passions, and be susceptible to illusions; for we owe most of our pleasures to illusions, and unhappy is the one who has lost them. Far then, from seeking to make them disappear by the torch of reason, let us try to thicken the varnish that illusion lays on the majority of objects.

— Emilie Du Châtelet, Discourse on Happiness translated by I. Bour & J.P. Zinsser, p. 349.

I think this idea of the truth being best told at a slant, of illusions being necessary is compelling but slippery. How do you distinguish illusion from falsehood? In the case of self-illusion, a truth one keeps slant from oneself, there is an air of paradox: in order to maintain an illusion about a truth, surely one must apprehend that truth. In the case of maintaining an illusion for the sake of others, there are thorny moral issues. Isn’t it, at best, paternalistic to decide that another person cannot handle the truth? And at worst, maintenance of an illusion turns into straightforward manipulation.

Du Châtelet then, given she has forsworn prejudice and immorality in her quest for happiness, must be careful about illusion. In her discussion she gives us two models. The first is optical illusion.

Such are optical illusions: now optics does not deceive us, although it does not allow us to see objects as they are, because it makes us see them in the manner necessary for them to be useful to us.

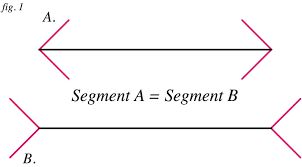

Take as an example the Müller-Lyer illusion.

These two lines appear to be of different sizes, but measurement reveals them to be identical. There are different hypotheses explaining the illusion, but they cohere with Du Châtelet’s point: the illusion is a side effect of some general heuristic in visual processing that usually works quite well.

Indeed, Du Châtelet is making a stronger point. We do not see objects as they are. Rather, our perception is mediated, inferential and adapted to our environments. In this view, there is no categorical difference between illusion and normal perception. Rather the difference is practical: with illusion our normal perceptual equipment pushes us in the wrong direction. Its not the perception itself but its consequences that constitute the illusion.

It is only with this stronger sense that we can think of illusions being useful. And even then, it is not so much that illusions are themselves useful. Rather, the perceptual system is useful, subject to illusions, and would actually be less useful were it less subject to illusions. That is, the best way to forestall illusions would be to more skeptical or to expend more effort on discrimination: each of which is costly.

Fortunately, Du Châtelet’s next model is explored in more depth. She asks.

Would we have a moment of pleasure at the theater if we did not lend ourselves to the illusion that makes us see famous individuals that we know have been dead for a long time, speaking in Alexandrine verse?

That is, with stories, we “lend ourselves” or play along with an illusion. Of course, we know that what we see in a theater or on a TV screen is not really happening. Some part of this knowledge remains operative at all times: we might cry at a death on stage, but would never leap out of our red velvet chairs to prevent it.

Taking these two models together, we can see two aspects to this ability, being susceptible to illusions, emerge. On the negative side, there is restricting one’s attention, keeping things out of mind. When driving, simply don’t consider the possibility of crashing. The better part of optimism is ignoring the worst that can happen. As Du Châtelet puts it.

We can choose not to go behind the set, to see the wheels that make flight, and the other machines of theatrical productions.

And then on the positive side, we can play along with a pretense. To use her own melancholic example, we can, as a romantic affair peters off, “love for two” and act as if, allow ourselves to imagine, that it is as strong as its halcyon days.

This example plunges us back into the interpersonal and the normative. Perhaps it is best for the person still in love to ignore signs of decay, to act as if the romance may be revived (who knows, perhaps it can be). Yet, surely, it is cruel and cowardly for the other party to participate in these illusions. And this leads us, circuitously, back to Dickinson.

On the surface, Dickinson’s lyric is advancing something like Du Châtelet’s case. Tell the truth, sure, but not nothing but the truth. The audience simply cannot handle the truth. However, the lack of further context introduces a deep ambiguity. We do not know who the speaker is, who the subject is, what kind of truths are on the table. The fact that “all the truth” becomes “the Truth’s superb surprise,” suggests we’re talking about truths of the upmost importance: metaphysical, theological truths perhaps.

At stake is not just the telling of the truth, but controlling how the truth is received. By the third couplet, it is not entirely clear that we are considering telling the whole truth.

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

Here Truth takes on a terrifying aspect as lightning. And at the same time, the subject loses their direct authority on truth. The lightning is happening outside of the subject’s control; the children can see it. They just don’t really know what they’re looking at it. Instead, the subject is made interpreter of the truth. They’re not really telling the truth at all, only offering an account of the truth.

This gets us into the heart of the ambiguity of this poem. While it’s fairly clear what is being said, nothing is given about who is speaking to whom. At most we can tell that the truths in question are a matter of some import: capital T truths, truths which dazzle and surprise, which are as lightning. But we don’t enough to tell if this is good advice.

And if it is just good advice, well, that’s not really telling it slant is it? The poem becomes a straightforward account of the importance of obliqueness. How unsatisfying. We can suppose instead that it is bad advice. Okay. Who knows this?

The speaker knows it’s bad advice, but the subject does not. What we have here then is an act of manipulation. The speaker wants to control the speaker, to hold them back from plainly speaking their truth.

The subject knows it’s bad advice, but the speaker does not. A farce results. The speaker is prattling on, making a fool of themselves, when we really should know: the truth is simple and best told simply.

Both know it’s bad advice. Perhaps this is bad advice that they have both received and are commiserating by reciting it ironically. Or a private joke.

What shall we do with such deep ambiguities as these. I confess they may be too deep for my infirm delight. At the least, they do meld into some stable super position but alternate and chase one another. Each line appears at first one way and then flits into some other tone. It is best to take Du Châtelet’s advice not just for living but for reading as well. Pick your favorite illusion and run with it.

I think Emily Dickinson is speaking about how should the parents tell kids about the world, as to allow them to feel safe and confident.